Where are we with the On-Farm Experimentation Process in Côte d’Ivoire?

A follow-up engagement with farmers and stakeholders provides key pointers

Working under the auspices of the Nutrient Catalyzed Transformation (NUTCAT) on-farm experiment (OFE) project initiated by APNI, a post-harvest dialogue (PHD) meeting of farmers and other agricultural stakeholders from Poro, Tchologo, and Bagoué regions was held in Korhogo, northern Côte d’Ivoire. Participants deliberated on issues that affected maize production in the recently concluded season. This was a follow-up workshop to the first of its kind held one year ago. Hence, this engagement provided the opportunity to build on the initial operationalization of the OFE platform within the NUTCAT project.

“After last year’s PHD, we had a better understanding of how farmers were learning from each other and from researchers / extension and how this learning was going to influence their on-farm decision-making and experimentation processes,” remarked APNI Scientist Dr. Ivan Adolwa.The aim of this recent PHD was to build on these initial lessons by assessing how farmers implemented management changes on their fields in the second season, what they learned in the process and whether they shared these learnings with other farmers or stakeholders. The maize improvement team (MIT) also used this opportunity to review the second season, which was further enhanced with the added perspective of farmers.

The event gathered farmers who participated in the first and second seasons of NUTCAT as well as interested farmers who were not yet involved. Other stakeholders from the National Agency for Rural Development (ANADER), the Federation of Maize Producers of Cote d’Ivoire (FEMACI), OCP-Cote d’Ivoire, and APNI were also enjoined in the meeting. As in previous meeting, focus group discussions and in-depth interviews supported by agronomic and remote sensing evidence was the approach used to guide the discussions and collect useful data.

Skills competency of farmers in northern Côte d’Ivoire

Using a competency-based tool[1], they assessed the skills competency levels of farmers who now have been through two iterations of the OFE process. The main competency being assessed here is on the capacity of these smallholder farmers to continuously learn and innovate on their farms using the available (often scarce) resources. There was behavioral evidence on the ability to test solutions given that most farmers tried new fertilizer timing and application methods. Farmers were interested in the aspect of cropping densities with most trialing new sowing methods that adhere to optimal densities. The smallholders also trialed improved maize seed varieties and adhered to good agricultural practices such as weeding (where they could afford labour or herbicides). Their verdict was that these new practices were better than preceding ones as evidenced by their decisions to increase the scale of implementation and share their experiences with other farmers within and beyond their village. This, however, provides only a snapshot of a probable behavioral change process. Therefore, more detailed data collection and subsequent analysis entailing (but not limited to) surveys will be conducted to complement this investigation.

OFE as a precursor to management change in smallholder farmer systems

The focus group discussions further elucidated the management and technological changes implemented by NUTCAT farmers. As mentioned earlier, improved seed and fertilizers were tested. Interestingly, farmers are learning and trying out new fertilization techniques as guided by 4R principles. For instance, fertilizer timing and placement methods are being tested by farmers. A NUTCAT farmer, attested to better yield performance when these new management techniques (borrowed from the benchmark OTs) are applied. However, a major factor affecting fertilizer trialing by farmers is that of lack of timely access to the inputs and their prohibitive cost.

“Farmers are observant and will out of curiosity test new technologies and practices. One farmer noticed that a neighbour’s maize crop was quite robust, so he enquired on the ‘secret’ he was using,” noted Adolwa.

This ‘secret’ was an improved seed variety, which according to the farmer resulted in better yields. Nevertheless, the same farmer mentioned that improved seed varieties are more susceptible to armyworm attack than traditional ones. Boundary effects were also mentioned, with one farmer explaining that the cotton he grew next to his maize field hindered its production. Presence of cattle and fall armyworm-infested fields of neighbours are similarly a hindrance to maize production.

Non-NUTCAT farmers have also followed closely what is happening in the benchmark OT fields as well as FP fields. They attest to trialing improved seed technology, which according to them has resulted in better yields. Others are still observing if NUTCAT farmers will get better yields. The use of right spacing (cropping density) and herbicides have also been implemented by these farmers.

“It will be useful to complement this information with surveys and monitoring data to have more concrete evidence that farmers are adjusting their management practices based on their observations and experimentation. This additional data triangulation will take place throughout the third season of the project,” explains APNI Scientist, Dr. Thérèse Agneroh.

Spotlight on the innovation-decision process in northern Cote d’Ivoire maize systems

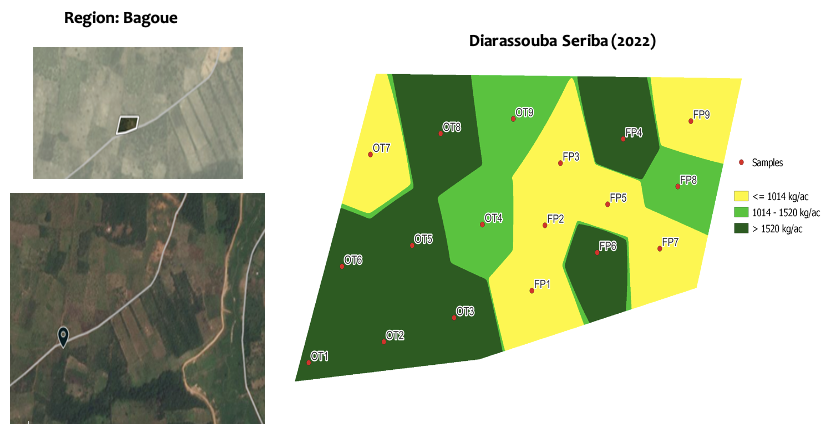

Discussions with farmers brought out the nuances of farmers’ information uncertainties and learning, interactions with digital tools (imageries), decision-making, and returns on investment (ROI) when they use technologies. The digital imageries (PlanetScope and Yield maps) were in alignment with farmer knowledge of variability within their fields. Interestingly, farmers have devised ways of dealing with the variability e.g., intensifying production or simply shifting to better land. Below is an extract from a farmer based in Bagoue region.

“I agree with the pictures, the analysis proved that most of the land was rocky, I am satisfied with the picture. But I want to know if APNI can allow me to change the land. Growing the seed on the same land over successive years, the yield will decrease.”

Natural color images captured with PlanetScope (late growth season October 2022) and yield maps (left) of a farmer’s field in Bagoue region.

Whether digital imageries, presently and in the future, could be effective channels for learning on how to improve management in heterogenous landscapes is still an issue that warrants further investigation. Meanwhile, farmers are currently learning through videos, local radio stations, research agencies, local extension, and NGOs. One farmer mentioned that they use the internet to view videos of some farms in China.

The farmers also have an awareness of what this variability (in soil fertility) costs them in economic and other quantifiable terms. One NUTCAT farmer, for example, quantified a loss to the tune of 100,000 CFA due to the patchy performance of his FP. In general, farmers are highly incentivized when they expect a high ROI. The foremost concern, however, for farmers was the unavailability of fertilizer and seed inputs at the required time. Another pressing issue for them was on how to effectively control Spodoptera frugiperda or “the legendary bug” attacks. Therefore, the decisions farmers made during the season were mainly determined by the extent to which translational (availability of inputs), temporal (likelihood of crop destruction by armyworms) and even metric (incomes, ROI) uncertainties were addressed. For instance, despite learning about 4R Nutrient Stewardship they were not able to apply fertilizer appropriately because they did not get fertilizers on time. The premise of these farmers is that if inputs are made available on time, they are likely to realise high yields at the end of the season. As mentioned earlier, a better understanding of how these information uncertainties affect farmer decisions and ultimately the outcomes of smallholder farmer enterprises will be further enhanced with additional data from surveys and monitoring exercises.

Deliberations of the Cote d’Ivoire Maize Improvement Team

The MIT is an important platform within the NUTCAT project as it leads the process of establishing, evaluating, and updating input and crop management practices in the benchmark optimized treatments. The MIT is envisaged as a vehicle to mainstream improved crop nutrition management that is backed up by an OFE process, in national agricultural research and extension systems. The MIT is composed of the following stakeholders: ANADER, FEMACI, OCP-CI, APNI and farmer representatives.

One of the main challenges of the past season was the rampant attack by the pest Spodoptera frugiperda commonly referred to as Fall Armyworm. One of the ways of controlling these pests is to sowiat the right time. But with climate change, as evidenced by irregular rainfall patterns, it is difficult to know the right time to plant. Therefore, the MIT envisage that the best option is to develop resistant maize varieties given that Fall Armyworm have developed resistance to chemicals. Consequently, MIT has decided to enjoin a breeder from the CNRA (the National Research Institute) that will help in developing these varieties. Lack of labour, especially for weeding, and the unavailability of fertilizers when required are issues that will be addressed by MIT going forward.

[1] Catholic Relief Services. “SMART Skills Competency Model.” Baltimore: CRS, 2021.

APNI contributors: Dr. Ivan S. Adolwa, Farming System Scientist; Dr. Thérèse Agneroh, Scientist